Mental Health: Supporting Students Now

In September 2022, Esther Akinlosotu will kick off her second year at the University of Manchester, diving into the modern history courses she loves.

Esther Akinlosotu, a student at the University of Manchester.

But the road here, she says, has been challenging. Akinlosotu spent her last year and a half of secondary school in remote classes at home in London during the height of COVID-19. Tackling the A-levels—qualifying exams for university in the U.K.—was tough because she (like many students who graduated during the pandemic) missed out on key skill-building. Navigating the coursework, adjusting to in-person interactions at Manchester—it was overwhelming, she says.

“The pandemic was really the first time where I experienced feelings of things like depression and anxiety, and I was really confused,” says Akinlosotu, a self-described perfectionist and extrovert. She’s now learned to pay attention to her mental health, take breaks, and pursue hobbies: “I tell myself: You’re a person first and then a student.”

Like Akinlosotu, students around the globe are navigating—and many are profoundly struggling with—mental, social, and academic pressures. Rates of mental health issues like anxiety and depression among students have been rising for more than a decade, exacerbated in some ways by the pandemic. In response, schools, colleges, and universities across the globe are acting with new urgency to open conversations about and launch new supports for mental health.

Here’s a snapshot of student mental health now—and how advancement teams are working to boost students’ wellness by raising awareness and sharing information, mobilizing donor and alumni support, and promoting belonging.

Student Mental Health Today

For Akinlosotu’s generation of students, coping with pandemic stress has taken a toll. Globally, the pandemic spiked anxiety and depression 25% across all age groups—but young people have been particularly impacted, notes the World Health Organization. Research from the Center for Collegiate Mental Health at Penn State, U.S., (among many other studies) indicated moderate to substantial increases in students’ academic and family distress, social anxiety, and disordered eating from fall 2020 to fall 2021. In its reporting on rising teen suicide rates, the New York Times called declining youth mental wellness the “inner pandemic.”

But the issue goes beyond COVID: We’re in the midst of a broader mental health crisis for young adults and adolescents that’s grown in the last decade, explains Sarah K. Lipson, a Boston University researcher. Globally, one in seven 10 to 19-year-olds experience mental health issues, WHO data indicate. The number of students with one or more mental health conditions has doubled since 2013, according to the Healthy Minds Network, which has collected 15 years of data on student mental health from 500+ institutions. Since then, symptoms of depression and anxiety in young people have increased 135% and 110%, respectively. This is more pronounced in specific groups, Lipson says: “The largest inequalities we see in prevalence are among LGBTQ+, particularly trans and nonbinary, students—60% of them screen positive for symptoms of depression.”

AWARENESS AND UNDERSTANDING: Boston University researcher Sarah K. Lipson says everyone on a campus (students, faculty, staff, and leadership) should be aware of the mental health resources available on campus or in the local community.

Without support or treatment, students with mental health issues are likelier to struggle academically or drop out. And though the number of young people seeking mental health care has jumped up 24% since 2013, there’s still a treatment gap, explains Lipson. Low-income students, international students, and students of color are less likely to seek treatment.

What’s driving the surge in mental distress? It’s hard to pinpoint. In a 2022 College Pulse Student Voice survey, students listed keeping up with coursework, pressure to succeed, finances, and balancing work/family as their biggest stressors. But COVID-19, racism, climate change, and geopolitical events like the Ukraine invasion also made the list.

“It’s hard to quantify the effects of the pandemic, or racial trauma, or political challenges, or unrelenting uncertainty. But what we see is that problems have really amplified,” says Lipson.

For years, colleges and universities have supported student mental health with counseling services, wellness programs, and training for faculty and staff—but now many institutions are acting with new urgency to expand those supports. Governments are taking action too: In June, the U.K. government announced a £3 million investment to close mental health treatment gaps at universities. Since 2020, the U.S. has distributed $76 billion in emergency funds to colleges through the federal American Rescue Plan to launch supports like mental health hotlines.

Mobilizing Support

At institutions around the globe, advancement professionals are part of this multilayer effort to support students. Most notably, advancement teams are at the forefront of activating support for emergency funds and expanded mental health programs.

Amid the pandemic and before it, many institutions made wellness a fundraising priority. For example, Kansas State University in the U.S. is using a $10.2 million gift to create a center for student wellness; St George’s, University of London created a Mental Health and Wellbeing Fund in 2018 and leveraged it to hire a welfare support officer; and Canada’s Brock University raised $250,000 in 2020 to expand its wellness services and hire more clinical support staff.

Funding more staff positions is crucial at many campuses because demand for counseling is up. In 2019, 87% of campus counseling centers in the U.S. reported an increase in demand, according to the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors.

At Canada’s Toronto Metropolitan University, that was the case too: More than 2,200 students (5% of the university’s 45,000 students) visited the university’s counseling center in the 2018/2019 session, and the team there had already seen a 46% demand increase the following year. So, TMU’s advancement team devoted its November 2019 Giving Tuesday campaign to mental health, raising $22,556 that allowed the university to hire a second clinical psychology resident for the counseling center.

Research has shown that more diverse counselors are key to helping close the treatment gap for Black students and students of color. So, to serve its diverse student body, TMU has worked to diversify counseling staff to have “representation that students can identify with,” says Allison Urowitz, Executive Director of Advancement. Part of Urowitz’s team’s work involves building access for underserved students: 25% of TMU students are first-generation and 70% are eligible for some form of financial assistance from the province.

“We look at social determinants of health and that includes whether there are socioeconomic barriers that students are facing. Building out financial access complements other efforts to holistically support student health and well-being,” she says.

The link between financial support and mental health is one the advancement team at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia, reinforced early in the pandemic too. In 2020, the country’s COVID-19 lockdown restrictions and curfew were intense—earning it the nickname “fortress Australia,” says Jimmy Buck, Chief Advancement Officer.

“There was this concentrated anxiety that added a level of stress and complexity for our students that, unless you were physically here, it’s hard to understand from the outside,” he explains.

Many students lost their service industry jobs, and international students were cut off from government support. Deakin’s scholarships office was inundated with requests for financial support, and in their applications, many students wrote about how worried they were about paying rent or affording groceries. Buck’s team launched the emergency assistance fund to address urgent student needs—supporting more than 1,000 students, including international students.

Financial support like this sends students a message about overall wellness, says Buck.

“When you support a student with a donation, you’re not just supporting them financially,” he says. “The act of giving indicates for that individual: I care about you and I want to back your success.”

Raising Awareness

Another piece in the mental health puzzle is helping students understand and access supports.

According to Healthy Minds data, 64% of college students who screen positive for mental health symptoms aren’t receiving care. Nearly a quarter of students say they don’t have time to seek help, but 30% say they wouldn’t know where to access resources.

It’s key for universities to convey how “taking the time to address your mental health is going to make you a better learner,” says Lipson. “A lot of students feel like they’re just too inundated and overwhelmed to prioritize mental health. The task of seeking mental health services is easily procrastinated—there are immediate, known costs in the form of time and, potentially, discomfort. And the benefits are uncertain or in the future. We need to reach students with mental health resources in their daily routines.”

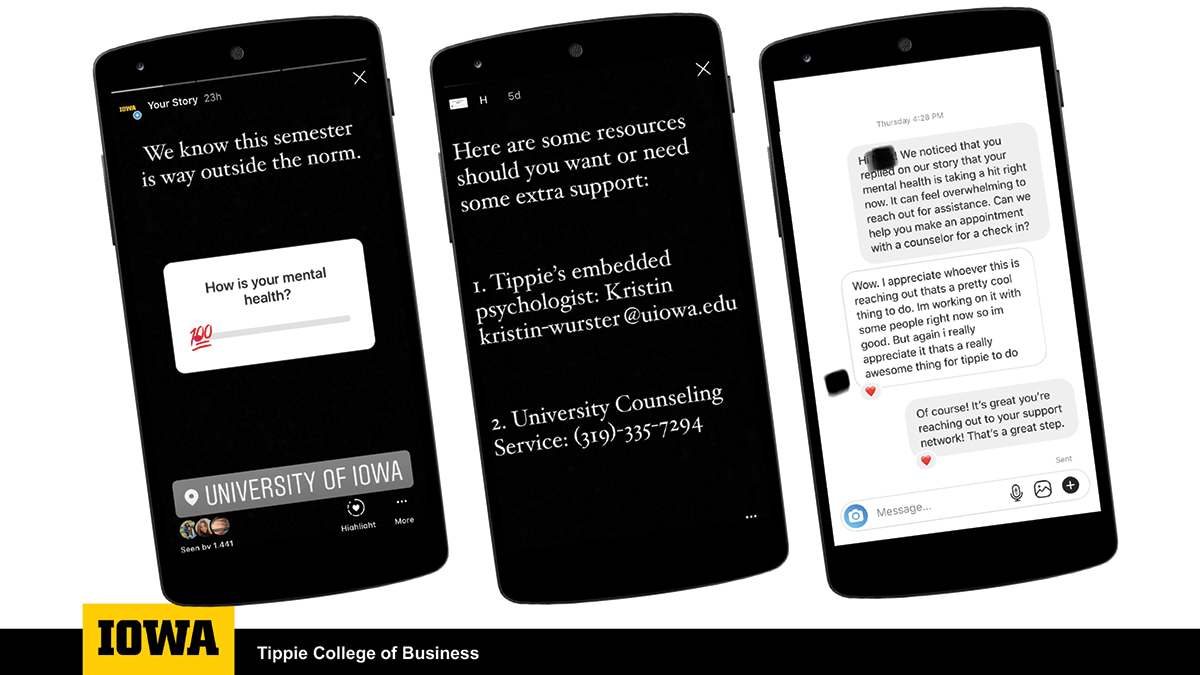

One way to address that? Reach students with social media. The University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business turned to Instagram for its “How Is Your Mental Health?” project. In early 2020, the Iowa City, Iowa, U.S., college hired an embedded therapist for business students. Rebekah Tilley, Director of Strategic Communications, convened her student team to brainstorm how to share information about the new counselor and raise awareness about mental wellness.

CHECKING IN WITH STUDENTS: The University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business used Instagram to ask students about their mental health and personally direct students to resources like counseling.

Using Instagram Stories, Tippie asked students to rate their mental health on a sliding scale during midterms (and grim fall weather) when students might feel more isolated, explained Tilley. Of the viewers that saw the Story, 7% (more than 100 individuals) rated their mental health as zero. Tilley and her team responded to each of them, saying: “Hi, [name]! We noticed that you replied to our story that your mental health is taking a hit right now. It can feel overwhelming to reach out for assistance. Can we help you make an appointment with a counselor?”

“We thought about how sometimes you have to acknowledge to yourself that you’re struggling before you can seek resources. How do we help students check in with themselves and make that realization?” she says. “[Campus communicators] are probably in the best position to normalize seeking out mental health therapy, if it’s needed. That’s because we can do it on a mass communication scale.”

Similarly, at the University of Manchester, the student communications team has undertaken broad messaging campaigns for students about suicide prevention (tagline: “You’re not alone”) and harm reduction around drugs and alcohol. The tone, explains Head of Student Communications Kim Graakjaer, is factual and honest.

“The key role we play is translating information in a way that students will connect with it and identifying channels that will reach and engage students,” she says. “Our role is partnering with those practitioners and colleagues to ensure that what they need to convey gets through in the best and the right way.”

Plus, students themselves can offer feedback on mental health messaging. Manchester develops each of its mental health campaigns in partnership with students from the 100-member Student Perspectives Panel. The panel, says Graakjaer, is a deliberate cross section of student voices: undergraduates, graduate and international students, commuters, individuals with disabilities, and more.

Building Relationships and Community

Positive social ties can help students cope with stress and isolation. The University of Manchester gives students six suggestions for well-being, and one is connecting with others. Graakjaer’s student communications team also shares messaging, like in its “Look Out for Your Mates” campaign, to encourage students to support one another.

Support for Students: The University of Manchester uses social media and messaging campaigns to connect

students with mental health resources.

Other universities have turned to alumni to help build community and offer students guidance. In 2020, at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, more than 500 students and 100 alumni joined Pentacell, a mentoring program recognized with a 2022 CASE Circle of Excellence Award. Over the course of a school year, each Pentacell group (five students and one alumni facilitator) meets 10 times virtually. It’s a collaboration between the alumni team and the counseling service, born out of a need for a “non-clinical intervention to increase well-being, belonging, and alleviate stress and anxiety,” says Alice Perry, Head of Alumni Relations and Annual Giving.

The feedback has been “phenomenal,” says Perry: “People really appreciated that ability to connect and the friendship they got with it. Someone called it a game-changer, [saying] that they wouldn’t have gotten through the [university] experience without it.”

MENTORING AND GUIDANCE: The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s Pentacell mentoring program helps students and alumni build relationships.

Pentacell has forged relationships at a time when participants (many of them essential medical workers) faced unprecedented strain. It has also connected students of diverse backgrounds across the globe: Half the student participants hail from outside the U.K., and alumni facilitators live in 45 different countries.

Institutions can work to foster belonging and inclusion in a variety of ways—but intentional wellness supports are even more important for students of color, who bear the mental ramifications of racism and prejudice but are less likely to seek treatment than their peers. At Manchester, Akinlosotu (who’s Nigerian; her parents migrated to England) says that being often the only Black student in her classes is isolating.

“You feel like you’re not meant to be here, and that really weighs on your mind,” she says.

Driven to support her fellow students, she volunteers at the Manchester Student Union as an ambassador for the Black and Minority Ethnic Students Campaign. But, she stresses, various groups of students are navigating different mental health issues—Black students may need or want different supports than LGBTQ+ students, for instance. Any decisions about student wellness should “include diversity, equity, and inclusion every step of the way,” she says.

An example of that in action: Toronto Metropolitan’s equity groups. To help address the support gap for students, TMU offers mentoring programs for specific equity groups (including Black, Indigenous, or LGBTQ+ students) to connect and share common experiences. Students who participate in these groups are more likely to use the university’s health and well-being services, university data indicates, says Urowitz.

Saturation Approach

Today, many universities have positioned mental health as an institution-wide priority. It’s a pillar of the University of Iowa and TMU strategic plans, for instance. That means everyone in an institution’s community, including advancement staff, are part of supporting mental health.

“When we have prevalence rates [for mental health issues] like we’re seeing, we can no longer use a targeted approach—we need a saturation approach, where every single person on campus has basic knowledge related to mental health,” says Lipson, the researcher. Anyone in contact with students could offer assistance—and Lipson recommends mental health training for all students, faculty, and staff.

Beyond staff training, Graakjaer’s team at the University of Manchester works to “bring student-facing staff along with us” on mental health campaigns, like its harm reduction initiative. For instance, they position mental health communications resources visibly on the staff intranet.

Student mental health issues can’t be resolved with one great fundraising or messaging campaign. This will be an ongoing challenge for university staffs—especially as generations of students who weathered high school during the pandemic reach college age and nontraditional students continue to juggle family and work in an uncertain economy.

But the more campus communities prioritize mental health, the more normalized it becomes. The goal, suggests Graakjaer, should be to keep these conversations open and ongoing.

About the author(s)

Meredith Barnett is the Managing Editor at CASE.

Tags

Article appears in:

September - October 2022

Faculty Partnerships: How advancement officers can team up with faculty to drive fundraising success. Plus, explore supports for student mental health, lessons from new managers, cryptocurrency, and more.