Fundraising During a Crisis

If colleges and universities kept a blotter on reputational crises that threaten fundraising, it might read something like this:

- Pennsylvania State University: In November 2011, a grand jury report found that former football defensive coordinator Jerry Sandusky sexually abused several boys. The Board of Trustees quickly fired President Graham Spanier and famed head football coach Joe Paterno, who died two months later. Sandusky was found guilty of 45 criminal counts of child abuse and sentenced to no less than 30 years in prison. Penn State was in the middle of its biggest fundraising effort—its $2 billion "For the Future" campaign.

- Wilson College, Pennsylvania: In January 2013, the trustees of the private liberal arts institution—all female since its establishment in 1869—voted to enroll men in fall 2014. Faculty, students, and alumnae launched an Internet campaign, which went viral, to reverse the decision. Resistance organizer and former trustee Gretchen Van Ness charged that Wilson had violated state law, leading to multiple legal challenges. Meanwhile, the college was $31 million in debt over a campus facility renovation project and needed another $12 million to restore and expand its historic 1920s-era library, shuttered since fall 2011 due to a heating system failure.

- University of Virginia: Since her appointment in 2010 as the institution's first woman president, Teresa Sullivan has dealt with two student murders, a Rolling Stone exposé about an alleged gang rape at a fraternity—which was later disproved—her abrupt firing and rehiring, and the assault of an African-American student by white officers from a state agency, resulting in campus protests. Some of these crises occurred while UVA was in the midst of the $3 billion "Campaign for the University of Virginia."

A controversial decision or scandal can cause donors and alumni to revolt and withhold gifts. Mix a volatile situation with social media chatter and emotionally attached alumni, and a reputational crisis can hit any institution, says Davia Temin of Temin and Company, a New York City management consultancy focusing on reputation and crisis management. But institutions can keep catastrophe from harming fundraising. The key is to maintain donors' trust by knowing what, when, and how to communicate with them.

"Bad things happen to great institutions," says Teresa Valerio Parrot, principal of TVP Communications, a Colorado-based public relations agency focused on higher education. "Two rules of thumb are to tell the truth and be a leader."

In institutions we trust

Trust is the cornerstone of the donor-institution relationship. In a crisis, maintaining donors' confidence requires institutions to foster a sense of unity and open communication.

"Once donors know that leadership is in charge—and that they are listening and focusing on the right issues—they will stay with you," says Deborah Taft, senior executive vice president and managing director of the fundraising consultancy Grenzebach Glier and Associates. Even when administrators can't provide the full story, most people know when they are being stonewalled. "Donors and volunteers want to know that the school and its leaders are dealing with the problem and don't have their heads in the sand." A simple and honest "I don't know at this time, but we'll get back to you when we do" can suffice initially, but Taft suggests preparing talking points to use when donors have questions. "The point is to be responsive and transparent."

After the Rolling Stone rape story made headlines in November 2014, UVA was both responsive and transparent—while still fundraising. The institution proceeded with its holiday phonathon, over the objections of several administrators. "We saw it as an opportunity to keep communications going and objectively address sensitive issues," says Robert Sweeney, senior vice president for university advancement. Students were trained to answer questions about the crisis, and although they had the option of doing paperwork instead of making calls, all remained on the phones. "They explained the sexual assault prevention programs and support groups that were already in place as well as ways that we were handling misconduct," Sweeney says. Although student callers encountered a few angry constituents, most people were compassionate and supportive, asking how the students were doing and expressing sympathy over their difficult situation.

By January, when students returned to campus, the furor over the article and subsequent closing of fraternity and sorority houses had mostly subsided. The Greek houses reopened under new agreed-upon rules, and the Rolling Stone story had been debunked. Thanks to the phonathon and individually addressing alumni concerns, "that December we were up almost 32 percent in cash flow and 26 percent in new commitments," Sweeney says. In 2015, Sullivan secured a three-year renewal of her contract, reinforcing the support that students, faculty, and staff provided during a 2012 behind-the-scenes coup in which board members attempted to fire her. Says Sweeney: "When I asked how she manages these situations, she replied, ‘You can't act on feelings. You've got to take the institution's best interests at heart.'"

Appealing to donors' desires to do what's best for the university helped Carrie Collins during two episodes that threatened fundraising. Collins had seen controversial departures at two of her previous institutions, including the 2014 exit of athletic director Paul Klimitas, who had worked at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia for 38 years. "The circumstances of the departures could not be shared because they were personnel issues," says Collins, the new chief advancement officer at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. But the outcry "resulted in donors saying they were never going to give us another dime."

Collins responded that "the only ones who would be hurt by not giving were the ones who needed it the most—the students." Although gifts declined, donors eventually began giving again, thanks to a comprehensive communications plan that included personalized responses to specific correspondence and questions. Talking points—explaining the decision had been made by the entire board and not just one individual, such as the president; clarifying that the staff honestly did not know the details; and emphasizing student accomplishments and awards—also helped motivate donors. In the case of the University of the Sciences, Klimitas, the former administrator, continued to support the institution, financially and by attending events. "He wanted to stay in touch and continues to do so," Collins says.

Developing a plan Olivia Pope would approve

Creating a plan of action before a catastrophe hits is essential, Temin says. "How you communicate the right tone in the right way to the right groups" helps set the stage as events unfold. "You have all these voices in your ear—‘don't say this, don't do that' "—coming from lawyers, crisis consultants, and other stakeholders, which can result in rash decisions before all the facts are in. Things are rarely as innocuous or appalling as they may seem, especially at first.

"The worst time to try to get organized is when things happen," Taft adds. Create a crisis management blueprint beforehand that addresses the following:

Who are your constituents?

Stakeholders can range from foundations and volunteers to major donors and alumni. "You need to clearly delineate and develop a master list of constituents," Taft says. The list must be up to date, comprehensive, and easily accessible, with specific categories of supporters and responsible disseminators. A single missed communication to an important stakeholder could hurt public perception and future giving.

How will you communicate?

While efficient, email is not a cure-all. "Some groups still need to get phone calls," says Taft, a former development leader at Girl Scouts of the USA and Simmons College in Massachusetts. These might include older constituents, those who check email infrequently, or deeply involved volunteers. For major donors or stakeholders, schedule a visit from a development officer or administrator: Bad news is best received from a familiar face.

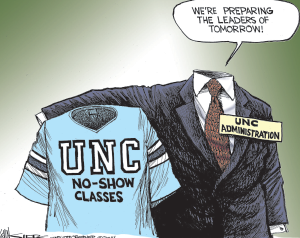

COMBATING CRITICISM: An academic scandal at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill opened the institution to ridicule and scrutiny in both local and national media. The carton ran in The Charlotte Observer. UNC deployed a phone tree to keep donors apprised of developments in an investigation involving student-athletes.

Personal connections helped University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill's fundraising survive a recent academic scandal. A 2011–14 investigation implicated a professor of African and Afro-American studies in giving student-athletes high marks in nonexistent classes so they could maintain player eligibility. "We organized a person-to-person phone tree," explains David Routh, vice chancellor for development. "Anytime a new piece of information became available, we activated a group of about 75 academics and development officers who would then schedule an internal conference call with a dozen or so of their top development contacts." The contacts then shared facts with roughly 1,000 important donors and other relevant parties.

"Each person was connected to their own network," Routh says. "Not only did it prevent a flood of inquiries, but it also provided accurate and complete information," mitigating potential misinterpretation and exaggeration of facts. As a result, gifts increased by 44 percent in fiscal year 2015, according to Routh.

Administrators at UNC and other institutions keyed in on a basic human trait: the impulse to reach out and help others during moments of need. Although circumstances vary, "many times donors will stay loyal through tough times," especially during an unforeseen disruption, observes Timothy Seiler, Rosso Fellow in Philanthropic Fundraising/Clinical Professor of Philanthropic Studies at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis.

"People realize that the institution is larger than one or two or even three individuals" and will be there long after they are not, Seiler says. For intentional decisions that cause controversy, such as going coed, "some people will leave, but others will remain because they believe the change will make the school stronger. They want to see it rebound from negativity" to an even more dynamic position.

How will you organize the sequence of communications?

Those closest to the institution—faculty and staff, administrators, trustees, students, and major donors—should receive information at the same time as the press or just before. "There needs to be a logical order, such as telling the board first, then the former board, then major volunteers, and so on," Taft says, "because it does matter to some people when they hear the news." Informing key donors empowers them to field inquiries from their friends, helps cement their support, and makes them part of the solution.

Peter Tombros, a retired pharmaceutical executive and the volunteer chair for Penn State's "For the Future" campaign, increased his pledge from $10 million to $15 million during the Sandusky crisis and, in an unprecedented move, remained as chair for the duration of the seven-year effort. "The last thing we needed was for it to look like I was quitting in the middle of a major scandal. I believed in Rod and his staff and knew they were doing a great job," he says, referring to Rodney Kirsch, Penn State's senior vice president of development and alumni relations. By April 2014, the university had raised more than $2.1 billion, two months ahead of the campaign closing date.

What roles should people take?

The development and communications teams need clear channels of responsibility and a consistent messaging philosophy. "You cannot wait until a crisis to decide to get along," Taft says. With that relationship intact, figure out who's responsible for which category of information and particular issue, she adds. Delegation is essential: One person can oversee the email list, while others communicate with various levels of donors, while still another fields questions from alumni.

Camilla Rawleigh joined Wilson College as vice president for institutional advancement just before the coed announcement. "I had to quickly figure out who I could turn to for support," she says. "At Wilson, there's a difference among graduating classes and how they react to events." Graduates of the 1940s, '50s, and '60s, for instance, seemed more accepting of change. Rawleigh sought champions who could help tailor messages for their respective classes. While a core group of alumnae remains vehemently opposed to admitting men, the college is on firmer footing both financially and in terms of enrollment, which increased 14 percent in fall 2014. The college recently renovated, rededicated, and reopened its library after a successful fundraising drive. Wilson exceeded its annual donor pledges for 2015 by $100,000.

It's important to be sensitive to the emotional needs of the staff when delegating. Penn State offered counseling, and Kirsch met with his team several times a day at the beginning and then weekly as the situation evolved, holding Q&A town halls as needed. Topics ranged from dealing with stress to handling the external media frenzy. Of the 375 development and alumni relations staff on board at that time, he says, "I don't know of anyone who left because of the scandal."

Both Kirsch and UVA's Sweeney found a sounding board in longtime friend Rhea Turteltaub, vice chancellor for external affairs at the University of California, Los Angeles. "A network of professional colleagues can shore you up during difficult times and provide new ideas and the benefits of their own institutional experience," says Turteltaub, who has developed an extensive network of contacts and addressed several crises during her 30-year fundraising career. "As hard as it may be to admit, we all need help sometimes."

Keep calm and carry on

Pleasing everyone is impossible. Despite Wilson's successful integration of men, the "Preserve Wilson for Women" movement continues, buoyed by Sweet Briar College alumnae's successful takeover of their Virginia alma mater.

"Not only have we received support from alumnae who previously had no involvement with Wilson but we have far from exhausted all legal avenues," says Van Ness, a lawyer who has helped spearhead the protest. The group has raised more than $150,000, and in February 2015 it filed an appeal with the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania. "There's still a great need for all-women's colleges, as evidenced by the millions raised in support of Sweet Briar and the fact that there's a waiting list for Bryn Mawr College," Van Ness says.

In the end, a crisis's impact on fundraising depends on how the institution handles the situation and communicates with key stakeholders. "As hard as it may be, you can't take anything personally," consultant Parrot says. "You need to remain objective, even in the face of tough feedback."

Many an institution has faced difficulties and will continue to do so, as UCLA's Turteltaub notes: "If leaders can own the problem and focus on the big picture, others will follow."

Bigger donors are more supportive

Communication runs both ways, and it's important for development staff to assess the feedback they receive. The loudest critics aren't necessarily the most invested: At Penn State, Rodney Kirsch, senior vice president of development and alumni relations, analyzed some 4,000 emails during the Sandusky crisis and discovered that donors who gave more than $5,000 were more likely to remain supportive than those who contributed less. "Many of the most negative comments were from people who had never even donated," Kirsch says. Penn State's decision to continue fundraising during the crisis was partially based on such metrics. "We wanted to reach out to alumni and let them decide for themselves."

Carrie Collins tracked correspondences after controversial departures at both Pennsylvania's Duquesne University and the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia and found similar results. "The vast majority of complaints," she says, "came from nondonors or those who had given small amounts many years ago."

Pennsylvania's Chatham University held a live-streamed town hall meeting featuring the president, trustees, and key alumnae to inform constituents about making the 145-year-old women's undergraduate college coed in 2014, says William Campbell, vice president for marketing and communications. The public meetings, blogs, and Facebook posts allowed Campbell to determine who was truly upset about the change. Instead of taking at face value the thousands of "likes" on a Facebook page, which could merely indicate bandwagon jumping, the team analyzed information from study groups, internal and external communication partners, and other data.

Like other institutions, they discovered a disconnect between what people said and what they did. "There was organized opposition, and while a few hundred were upset about the change, we moved quickly to address their concerns, even to the point of adjusting, within hours, key communications," Campbell says. They sent out letters that detailed "what we were doing, how we were doing it, and what the expected impact would be," to concerned alumni. The results: "We just completed our most successful capital campaign ever, and our undergraduate enrollment has doubled," Campbell says.

Even when donors withdraw their support, funding can come from other areas. "Although we lost some donors, we re-engaged others," says Camilla Rawleigh, vice president for institutional advancement at Wilson College, which angered some alumnae when it went coed. Some were waiting to see how the college would react to the firestorm. Once they saw that men were seamlessly incorporated into the fabric of the college and that academic offerings had been expanded, including adding master's degree programs in health care management, fine arts, and other fields, they opened up their pocketbooks. Staying in touch is important, even if potential donors are temporarily upset with the institution.

About the author(s)

Sandra Gurvis is a freelance writer who has published two books about the student protests of the 1960s: The Pipe Dreamers (Olmstead) and Where Have All the Flower Children Gone? (University Press of Mississippi).