Staying Ahead of Demographic Trends

In March, questionnaires for the 2020 Census began landing in mailboxes in the United States, followed by home visits from thousands of temporary field workers hired to supplement the decennial collection of statistics on the nation’s population.

From age, sex, race, and birthplace to household makeup, the census tabulates an array of demographic data that a wide range of industries and sectors rely upon for planning purposes, not the least of which are education institutions, which use the information to determine everything from course offerings to class sizes.

Far from static, populations shift and move constantly, and official census counts are meant to help planners reconcile estimates with actualities, in a virtuous cycle that resets every decade.

But in the day-to-day grind of work, finding time to pay attention to and incorporate such data into strategic planning and thought can be challenging. Ignoring these demographics, however, can present even more challenges for advancement professionals and the institutions that they serve.

“The world is in the midst of an unprecedented demographic transformation. The kinds of changes we find ourselves in—buckle your seatbelt because if you ignore them, you ignore them at your own peril,” James Johnson Jr., an expert on demographics and professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, told CASE commissioners at a November 2019 forum devoted to discussing horizon issues that will affect education institutions and advancement.

A stagnant birth rate. A burgeoning cohort of older adults. Migratory patterns from the Northeast and Midwest to the South and Southwest, where immigrants (largely from Latin America and Asia) are also settling. These are among the demographic changes that will be reshaping the U.S.—and to a large extent the world and the education sector—in the coming decades.

In response, institutions and their advancement offices are not only expanding their view on prospective students but working to ensure that their staffs and approaches to donors and other important constituents reflect the population as it is now and will be in the future.

As the World Ages

For a long time, the typical student profile at most universities and colleges (community colleges are the exception) has been young adults between the ages of 18 and 24, who attend classes full-time, often live on campus, and enjoy the financial support of family.

Myriad factors have disrupted the well-worn path from high school to college, some of which have been influenced by demographic changes. For the record, demography—the study of populations—can encompass many variables and disciplines, but by and large, the major units of analysis are birth and fertility rates, mortality and longevity rates, and migratory movements within the country and into the country.

Like other industrialized nations, the U.S. has been growing older, the result of people having fewer children (influenced, ironically, by better education) while medical and technological advancements have extended life spans.

In fact, 2018 saw the fewest babies born in any year since 1986, when the number of births began a long decline. Those under the age of 18 have accounted for a dwindling share of the nation since the early 1960s, when they made up 36% of the country; they are projected to be just 20% of the population by 2050. Meanwhile, the number of those 65 and older will nearly double, to 95 million, or a quarter of the population, by 2060, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. America’s rising age composition has been reflected in higher-education enrollments for some time. In 1970, about a quarter of students in degree-granting institutions were over the age of 25; this figure was roughly 40% in 2019.

Seeing the trend, many higher education institutions have been revising their strategies to capitalize on the silver tsunami. For example, Purchase College, located about 35 miles north of New York City, has always had strong linkages to its older adults, generations of whom have partaken in the school’s arts, theater, and enrichment courses, says interim President Dennis Craig.

In 2011, the college launched a project to bring senior citizens even closer to campus. Called Broadview, the 220-unit complex of apartments and houses will be situated on the southwest portion of the 500-acre college campus and open to anyone 62 and older, although the median age of those who have put down deposits is 77.

“We are emphasizing this is a learning community, not simply a retirement community, as there’s an incredible body of evidence to have both mind and body active for a long life,” says Craig, who notes that a learning commons will be located in the complex, enabling residents to enjoy student performances, art series, and other short-term classes.

Construction is slated to begin later this year, with residents moving onto the premises as early as 2021. Broadview will ultimately be a source of revenue for the college, bringing in a projected US$2 million in annual rental income, which will be earmarked for student scholarships and faculty additions.

“We’re very blessed that the generation entering Broadview has been very generous with philanthropic giving,” Craig says.

Not every university will be able to open a retirement community on campus, but institutions and advancement offices are adjusting their messages. Some offer courses that may lead to encore careers after retirement, or marketing materials that acknowledge the outsize role senior citizens are taking on in raising the next generation of students.

Hispanics, Immigrants Reshaping the United States Population

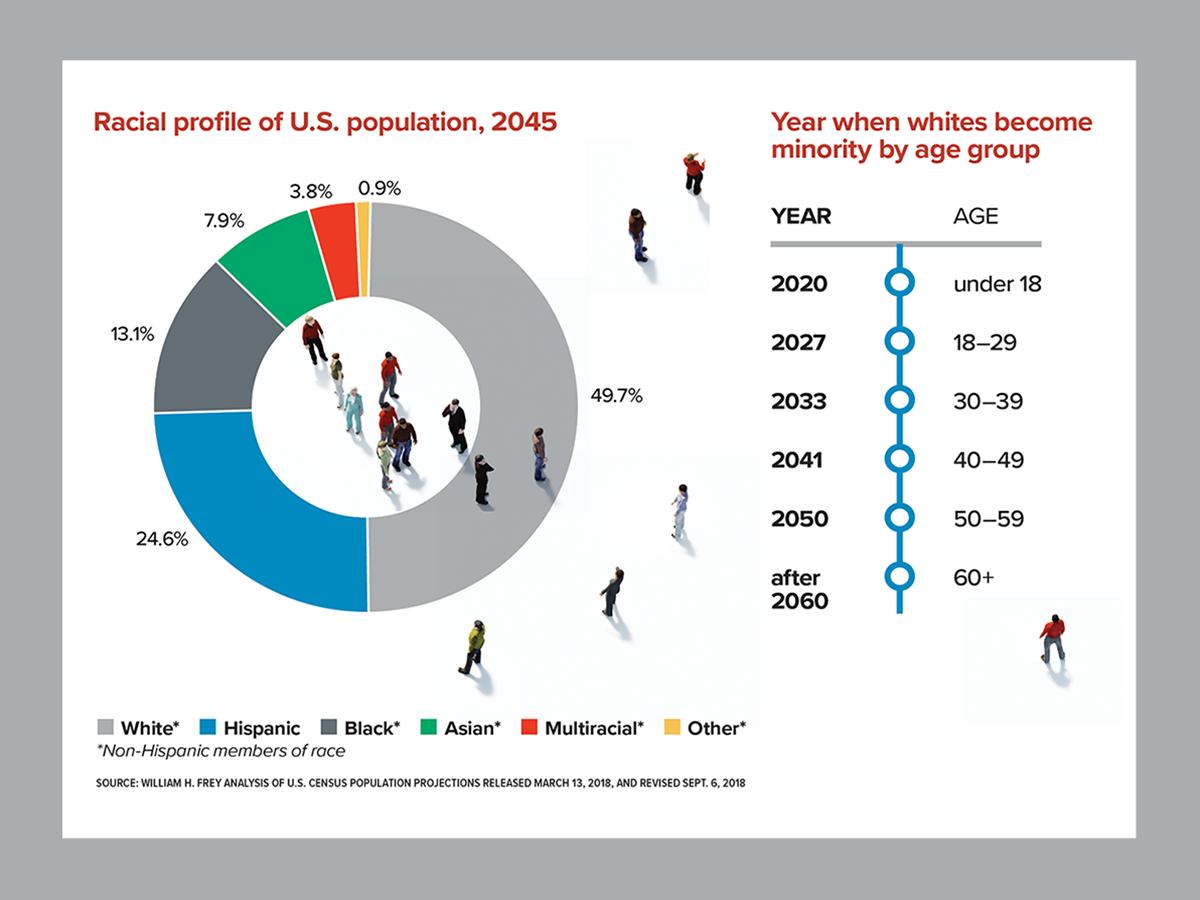

At the same time that the U.S. population grows older, it is becoming far more diverse. Census data estimate that in 2020, those under 18 will become the first generation in which racial and ethnic minorities constitute a majority.

Immigration influxes that doubled the number of foreign-born residents over the last three decades—most of whom hailed from Mexico—coupled with fertility rates among Latina women that are above the national average, have altered America’s population and turned Hispanics into one of the fastest-growing demographics in the country, particularly in the South. “The South has become the cat’s meow in terms of destination selection, and it is an importer of population from every other region of the country,” says Johnson, noting that the rise is due to a number of factors, including job growth, gravitation to warmer climates, and immigration.

In fact, migration patterns between 2010 and 2015 show the Northeast and Midwest losing nearly a million residents while the South gained 1.1 million, most of whom were white, though a sizable portion were black, Hispanic, or foreign born. The influx of new populations has forced institutions and advancement offices in the region to strengthen or create new fundraising streams that support language assistance programs and scholarships for students with an often lower income status than that of their traditional peers.

For example, just over half of the students at the University of Texas at San Antonio identify as Hispanic, many either immigrants or the children of immigrants. The university recently launched a $500 million investment campaign, with one priority being to raise scholarship money for students in a city with one of the highest poverty rates in the nation.

Some schools in the Northeast and Midwest are proactively reaching out to more populous regions of the country and the world. In addition, the U.S. is the top host of international students worldwide. In the 2018–19 school year, international students reached their highest number ever, nearly 1.1 million, the bulk of them from China and India. But new student enrollments have fallen recently amid trade tensions with China and other political uncertainties, according to the Institute of International Education.

Eastern Michigan University is trying to lure more international students to campus with a recently announced program that offers them in-state tuition and is trying to double their numbers by 2022. The university is part of a national marketing campaign to attract international students to U.S. higher education, called #YouAreWelcomeHere. The university’s marketing team has produced banners across campus highlighting students’ home countries as well as a video and website that feature international students.

In 2018, Muhlenberg College, a small private liberal arts college in Pennsylvania, hired its first two recruiters outside the region, in Atlanta and Los Angeles. Robert Springhall, vice president for enrollment management at Muhlenberg, says putting recruiters closer to the country’s hot growth spots not only enables them to visit more prospective students and high schools but also showcases Muhlenberg’s personality as a university.

“Putting people in the territories they’re recruiting lets us live what we say is one of the greatest benefits of the college: that we’re personal, that we care, that we can build these one-on-one relationships,” Springhall says.

For more reasons than one, attracting new kinds of students requires both insight and foresight.

A 2013 content analysis of recruiting materials from 165 four-year institutions found that U.S. universities regularly misrepresented the diversity of their campuses, showing double the proportion of black students in such materials, for instance, than were actually enrolled at the school.

“I’m seeing some colleges making a pivot perhaps without understanding what their strategy is, and I’m a little concerned for those colleagues, especially at schools that think there’s a singular answer to this change in demographics,” Springhall says.

What’s happening over the coming years, he says, is not going to be something for only the marketing or admissions departments to grapple with. Instead, the entire campus will have to think about how best to serve a new group of students who will have different needs and expectations.

As universities adjust to and prepare for demographic shifts in the country, advancement staff members are increasingly finding partners across campus to ensure that the entire student journey is a positive and memorable one.

Joe Buck, Lehigh University’s vice president for development and alumni relations, says the Pennsylvania liberal arts school has put a lot of effort into connecting with its first-generation students to make sure they get the most out of their college experience. Last year, the advancement and student affairs offices teamed up to organize a graduation brunch for first-generation students and their families, sending the invitation in five languages.

“It was one of the most touching events I’ve ever attended,” Buck says.

Aligning Alumni and Donor Strategies with Data

In order to raise funds among alumni, W. Kent Barnds, executive vice president of external relations at Illinois’ Augustana College, says it’s important to point out the generational and diversity transformations that are taking place on campus to help supporters understand the need for more scholarships focused on nontraditional students, such those who are the first in their family to go to college or immigrant students.

“I think we have to do a good job of describing how students today are having [an] incredibly different experience than those alumni who graduated 10, 20, 30, or 60 years ago,” he says. Not just demographic shifts but, more important, diligent recruitment efforts have changed the liberal arts college’s student makeup from 8.5% students of color in 2005 to 27% in 2019.

Fundraising professionals also need to understand how best to reach out to different generations when asking for gifts. Research from Nonprofits Source found that in giving across all areas, millennials are the most likely generation to contribute to work-sponsored initiatives, donate via mobile apps, and watch online videos before making a gift. Generation X donors prefer text messages and voice calls, and are the likeliest to volunteer. Boomers, while initially slow to adapt to technology, are responding to nearly all types of communication and are the most likely to make recurring donations. The Greatest Generation, born before 1946, prefers to give through direct mail campaigns and donate physical goods.

“The best communications are audience-centric. That means you need to meet your audiences where they are rather than assuming ‘if you build it they will come,’” says Tracey Temne, assistant vice president for strategic communications and marketing at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “We conduct research to better understand preferences and test our messages to ensure they are resonant and relevant to our ever-changing alumni and donor audiences.”

Staff, Faculty Representation Slower to Respond

Unfortunately, diversity among staff and faculty on college campuses has not kept up with the times. Just 12% of advancement professionals identify as nonwhite, according to a 2016 CASE survey. And about three-quarters of college faculty members are white, compared with 55% of undergraduates, the National Center for Education Statistics has found.

CASE is working to create a pipeline of diverse advancement professionals through two programs in the U.S. Its North American Fundraising Residency places recent graduates in yearlong entry-level positions in colleges across the country, while the internship program lets college students get a taste of the spectrum of advancement positions during a paid summer job at an institution.

But Angelique Grant, senior consultant and certified diversity recruiter with the philanthropy professionals search firm Aspen Leadership Group, says this work must go beyond diversity: “Diversity is counting heads, and inclusion is making those heads count,” she says. “If we’re not being inclusive, at some point no one will want to remain in advancement.”

Grant formerly served as assistant vice president for development at Florida International University in Miami, whose student body is more than 60% Hispanic. But when she began the job, only one or two people on the 15-member fundraising team were Hispanic. She made it a priority to diversify the team.

“Diverse gift officers bring unique perspectives to advancement,” she says. “If you focus on cultural contributions, your knowledge base is expanded, and the team can represent a wide range of life experiences. This is a situation we wouldn’t necessarily have had as a homogenous team.”

As they face demographic changes and challenges, advancement professionals say the most important tactic is to embrace these transformations in all facets of their work.

“Honestly, we just need to think about inclusion more holistically as we do everything,” says Barnds. “Rather than expect a more diverse population to join our club, we need to invite them to help shape the club to which we will all belong.”

Global Demographics

A look at how population shifts are affecting institutions around the world

Similar to U.S. trends, global demographics point to a decrease in birth rate, an increase in median age, and population numbers that are largely influenced by the movement of people—immigration into countries and emigration out. According to the Pew Research Center, the “global fertility rate is expected to be 1.9 births per woman by 2100, down from 2.5 today.” Paired with an increase in life expectancy, there will be an increase in the world’s median age. In 1950, the median age was 24. It is currently 31, and in 2100 it is projected to reach 42.

While the populations of Australia and New Zealand as well as Canada and the U.S. (thanks to an immigrant population that is expected to “see a net increase of 85 million over the next 80 years”) are projected to grow throughout the rest of the century, Africa will be the only region with strong population growth, according to Pew. Both Europe and Latin America are “expected to have declining populations by 2100.”

These demographic shifts point to a growing demand for higher education around the world. “Massification of Higher Education Revisited,” a research paper from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia, projects that “the total number of students in higher education is expected to reach nearly 380 million by 2030, 472 million by 2035, and more than 594 million by 2040—all up from roughly 216 million in 2016.”

Whether prompted by shifting demographics or not, many countries are expanding their international student programming and working to attract more of this type of student. Ireland, for example, has adopted a program meant to increase the number of international students studying in the country: the International Education Strategy 2016–2020.

Maria Gallo, founder and principal researcher at Keep in Touch Education—a social enterprise to support philanthropy research and alumni education—in Ireland, explains that while there are financial drivers, “diversifying higher education and internationalization to prepare all students to be active global citizens is also something that appears in institutions’ strategic plans” as those institutions work to meet the aims of the International Education Strategy.

Germany is also working to attract international students—though not only for financial reasons. Because over 20% of Germany’s population is 65 or older, the country needs to build up the younger generation to support its economy. “With one of the lowest birth rates in the world on one hand, and one of the longest life expectancies in the world on the other hand, younger people are needed, not only to keep the economy running, but also to even out this change in demographics,” says Marina Zielke, incoming students advisor in the international office of Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences. That’s part of the reason why Germany offers free tuition to international students—to entice them to complete their schooling in Germany and then stay on as members of the country’s workforce.

All study programs at Darmstadt are tuition-free for both German and international students. “Everyone, irrespective of their nationality, should be granted the same access to education,” says Zielke. And, according to a survey conducted by the German Academic Exchange, once these students are in Germany for schooling, they typically choose to stay and work in the country, at least for a few years. The survey found that about half of all international students plan to remain in Germany after graduation, with almost a third planning to stay permanently.

The enticement of free tuition seems to be working as the German Academic Exchange Service reports that the number of international students in Germany is continuing to increase. In 2017 there were 358,900 foreign students enrolled in German universities and that number rose to 374,580 in 2018.

Header photo credit: Alexander Spatari/Moment/Getty Images

About the author(s)

Barbara Ruben was a senior content creator at CASE.

Tags

Article appears in:

March - April 2020

Eureka! How institutions shine a light on the value of research. Also in this issue: multi-institution collaborations, demographic trends, and reevaluating traditional fundraising practices to engage women.